Content Index

- Tools: Gemini Anti-Gravity (Alley)

- Preparation and Architecture Concepts

- What are Clean Architectures and Clean Code?

- Clean Code vs Clean Architecture

- The Prompt and Refactoring

- Execution of the Plan

- The WebSocket Problem

- Result

- Interface Adapters

- Use Cases

- Entities

- Frameworks & Drivers

- In this folder, you can see the strongest implementation of technologies that are NOT ours and that we can change at any time, such as FastAPI and the database with SQLAlchemy.

We are going to perform a small experiment. We will take our current project, which doesn't exactly follow the best organizational practices -since it was born as a quick test to implement WebSockets- and we are going to improve its structure. We will do this following the best practices presented earlier in The lifecycle of a FastAPI app with Lifespan events

To do this, we will use established software architectures. I don't intend for this to be a deep course on Go or advanced architectures, but rather a presentation to pique your curiosity. Later, we can dedicate a full section or a specific course to it, or if you prefer, you can investigate on your own. This is the ideal time for this experiment, as the application is small and manageable.

Tools: Gemini Anti-Gravity (Alley)

For this work, I will use Gemini Anti-Gravity, the editor you see on screen. If you're not familiar with it, it's similar to tools like Windsurf or many others emerging today. It is a fork of VS Code that allows for more effective interaction with AI through agents integrated into the workspace.

One of its most interesting options is Planning. Unlike other extensions for VS Code, this tool generates a "roadmap" before applying any changes. This is extremely useful because it allows you to review and adjust the plan before the AI modifies your code.

Preparation and Architecture Concepts

Before asking the AI for global changes, it is essential to sync your project with GitHub. Things can go wrong, and having a backup will save you a lot of time if you need to revert changes.

What are Clean Architectures and Clean Code?

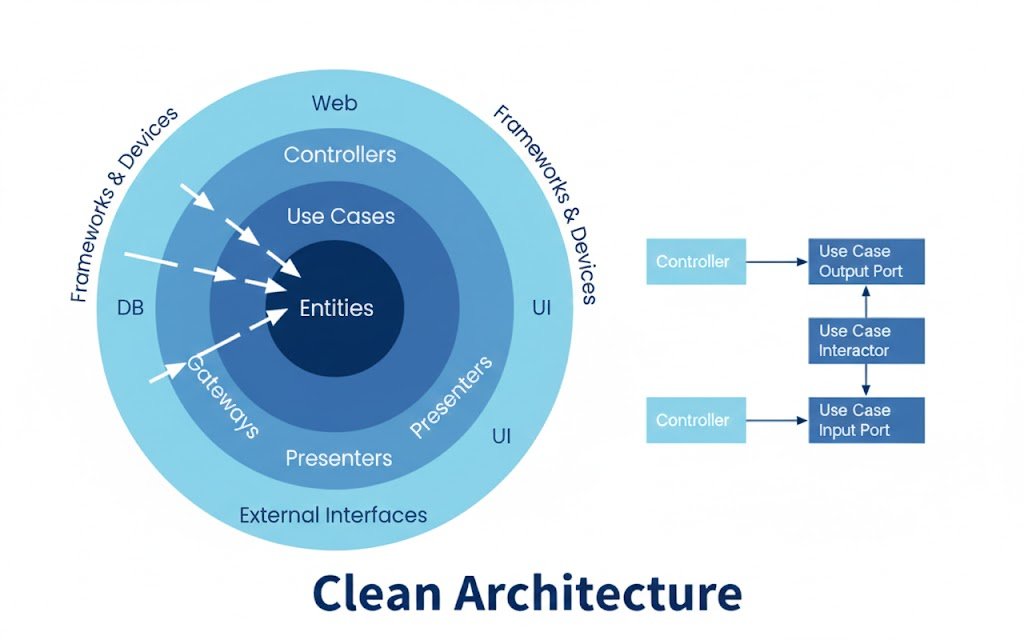

You have surely heard about Clean Architecture and Clean Code; let's see what each of them is.

Clean Code vs Clean Architecture

It is important to clarify something:

- Clean Code is not an architecture; it is a philosophy.

- It focuses on writing simple, modular, readable, and maintainable code.

- Clean Architecture is the practical application of those principles.

It's like the difference between API and REST API: one is the general concept and the other is its concrete application.

In essence, Clean Code involves ways of organizing code based on good principles. We have already applied some of this by separating schemas and models, but in an incomplete way. The idea of using an existing architecture is not to reinvent the wheel. Instead of inventing names for our folders, we use proven structures that make the code readable, maintainable, and scalable.

The structure we aim to generate is generally divided into:

- Entities: The purest business logic.

- Use Cases: Specific actions (e.g., creating a user, login). It is the heart of the business logic. Here, it is defined what happens when a user logs in, regardless of whether the request comes from a REST API or a WebSocket.

- This is where the actual system logic resides.

- For example, in login:

- We verify the user.

- We validate the password.

- We generate a token.

- Previously, this was inside the endpoint.

- Now it is decoupled.

- This allows it to:

- Not depend on the response type.

- Not depend on FastAPI.

- Be reusable.

- Interface Adapters: Controllers and repositories that translate data. They act as translators. Here are the controllers that receive HTTP requests and the repositories that handle data.

- They are the translators.

- They receive:

- HTTP Requests

- WebSockets

- XML

- JSON

- And they translate those inputs into use cases.

- Frameworks & Drivers: External tools such as the database or the web framework (FastAPI). This is where code that is "not ours" resides, such as FastAPI configuration or the database connection (SQLAlchemy). If tomorrow we want to change FastAPI for Flask, we should only have to touch this layer.

- Code that isn't ours goes here:

- FastAPI

- Database connection

- ORM

- Mongo, SQLite, Firebase, etc.

- If we change FastAPI for Flask tomorrow, the changes would be here.

- Code that isn't ours goes here:

The Prompt and Refactoring

For the AI to be effective, we need a good Prompt. I have used an AI to generate the instruction that we will give to our code agent. The result was the following:

"Act as a software architecture expert. Refactor my FastAPI application following Clean Code principles. Separate the code into Entities, Use Cases, Interfaces, and Adapters layers. Implement the Repository pattern for data access, ensuring that dependencies point inwards. Generate the new folder structure and the corresponding files."

Execution of the Plan

When activating the Planning option, the AI shows us which files it will create and which folders it will move. In this case, it will create a src folder with subfolders for entities, use cases (like login_use_case.py), and repositories.

The WebSocket Problem

During the refactoring, there was a small error with the WebSockets due to confusion between project versions. The AI initially generated a very simple socket that only returned text. I had to ask for a specific correction:

"Adapt the WebSocket endpoint called websocket_endpoint to the clean architecture, integrating the connection manager (ConnectionManager) we had previously."

Result

Let's look at some important code snippets to understand the previous structure:

A file in its simplest form which is the entry point of the application, where we access the controllers:

main.py

"""Application entry point."""

from src.frameworks_drivers.http.app import appsrc/frameworks_drivers/http/app.py

from src.interface_adapters.controllers import (

auth_controller,

alerts_controller,

rooms_controller,

websocket_controller

)

***

# Include routers with /api prefix

app.include_router(auth_controller.router, prefix="/api")

app.include_router(alerts_controller.router, prefix="/api")

app.include_router(rooms_controller.router, prefix="/api")Interface Adapters

Here are the controllers, which are the gateway to our app. Although it is true that it's impossible to comply 100% with Clean Code principles, there SHOULD NOT be any FastAPI code in this layer. Here we have the FastAPI controllers, which in short, following the MVC scheme, represent the intermediate control layer that connects the View with the Models:

src/interface_adapters/controllers/alerts_controller.py

@router.get("/alerts", response_model=List[Alert])

def get_alerts(

room_id: Optional[int] = None,

user: User = Depends(get_current_user),

alert_repo=Depends(get_alert_repository)

):

"""Get alerts endpoint with optional room filtering."""

use_case = GetAlertsUseCase(alert_repo)

alerts = use_case.execute(room_id=room_id)

# Convert entities to ORM-compatible format for Pydantic

return [

{

"id": alert.id,

"content": alert.content,

"created_at": alert.created_at,

"user_id": alert.user_id

}

for alert in alerts

]In the previous controller example, we see that the database is injected as a dependency because it could be anything: a MariaDB database, PSQL, a JSON file, Firebase, etc. By Clean Code principles, it is handled this way so that it is loosely coupled, meaning we can change the data source without breaking the controllers or other layers.

Additionally, we use use cases where the business logic is handled.

Use Cases

src/use_cases/auth/login.py

"""Login Use Case - Handles user authentication."""

from typing import Optional

import bcrypt

from src.entities.user import User

from src.entities.token import Token

from src.interface_adapters.repositories.repository_interfaces import (

UserRepositoryInterface,

TokenRepositoryInterface

)

class LoginUseCase:

"""Use case for user login."""

def __init__(

self,

user_repository: UserRepositoryInterface,

token_repository: TokenRepositoryInterface

):

self.user_repository = user_repository

self.token_repository = token_repository

def execute(self, username: str, password: str) -> Optional[str]:

"""

Execute login use case.

Args:

username: User's username

password: User's plain password

Returns:

Token key if successful, None otherwise

"""

# Get user by username

user = self.user_repository.get_by_username(username)

if not user:

return None

# Verify password

if not self._verify_password(password, user.password):

return None

# Get or create token

token = self.token_repository.get_by_user_id(user.id)

if not token:

import secrets

token = Token(

key=secrets.token_hex(20),

user_id=user.id

)

token = self.token_repository.create(token)

return token.key

@staticmethod

def _verify_password(plain_password: str, hashed_password: str) -> bool:

"""Verify password against hash."""

password_byte_enc = plain_password.encode('utf-8')

hashed_password_enc = hashed_password.encode('utf-8')

return bcrypt.checkpw(password_byte_enc, hashed_password_enc)In this module, we have our company or business logic. It doesn't care where the data comes from or the expected format. This layer uses a generic entity (neither Pydantic models nor the ORM). Since it's the business logic, in our case—an authenticated user—we handle the cases we covered in the REST API:

rest_api.py

@router.post("/login")

def login(request: schemas.LoginRequest, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

user = db.query(models.User).filter(models.User.username == request.username).first()

if not user:

return JSONResponse("User invalid", status_code=status.HTTP_401_UNAUTHORIZED)

if not verify_password(request.password, user.password):

return JSONResponse("Password invalid", status_code=status.HTTP_401_UNAUTHORIZED)

# Get or Create Token

token = db.query(models.Token).filter(models.Token.user_id == user.id).first()

if not token:

token = models.Token(user_id=user.id)

db.add(token)

db.commit()

db.refresh(token)

return {"token": f"Token_{token.key}"}But with greater abstraction. As mentioned before, Use Cases DON'T care about the data source (Database or otherwise) or the return type (which isn't specific, as we could use this use case for an API response—what we have—or from a Jinja template, etc.) and it uses a generic entity, again NOT coupled to any framework, which is the next layer.

Entities

We have 3 types of entities. The two we had in our FastAPI project that are strongly coupled to the technology, which in this example is FastAPI:

src/frameworks_drivers/db/orm_models.py

src/interface_adapters/presenters/schemas.py

These are defined in the ORM (strongly linked to code that isn't ours, like the database with SQLAlchemy) and the Pydantic schemas (which, although used by FastAPI, are by definition translators for the FastAPI project).

And finally, we have isolated classes, of the data class type, which just like in Kotlin are classes whose purpose is to present data:

src/entities

"""Alert entity - Core business model."""

from dataclasses import dataclass

from datetime import datetime

from typing import Optional

@dataclass

class Alert:

"""Alert entity representing a message in a room."""

id: Optional[int]

content: str

user_id: int

room_id: int

created_at: Optional[datetime] = NoneTherefore, following Clean Code principles, applications should have loose coupling. Thus, we can change the framework or technology (move to Django or Flask which DO NOT use Pydantic models) and the Use Cases will NOT be altered, which WOULD happen if we used a Pydantic class instead of these entities.

Frameworks & Drivers

In this folder, you can see the strongest implementation of technologies that are NOT ours and that we can change at any time, such as FastAPI and the database with SQLAlchemy.

Source code:

https://github.com/libredesarrollo/curso-libro-django-vue-channels